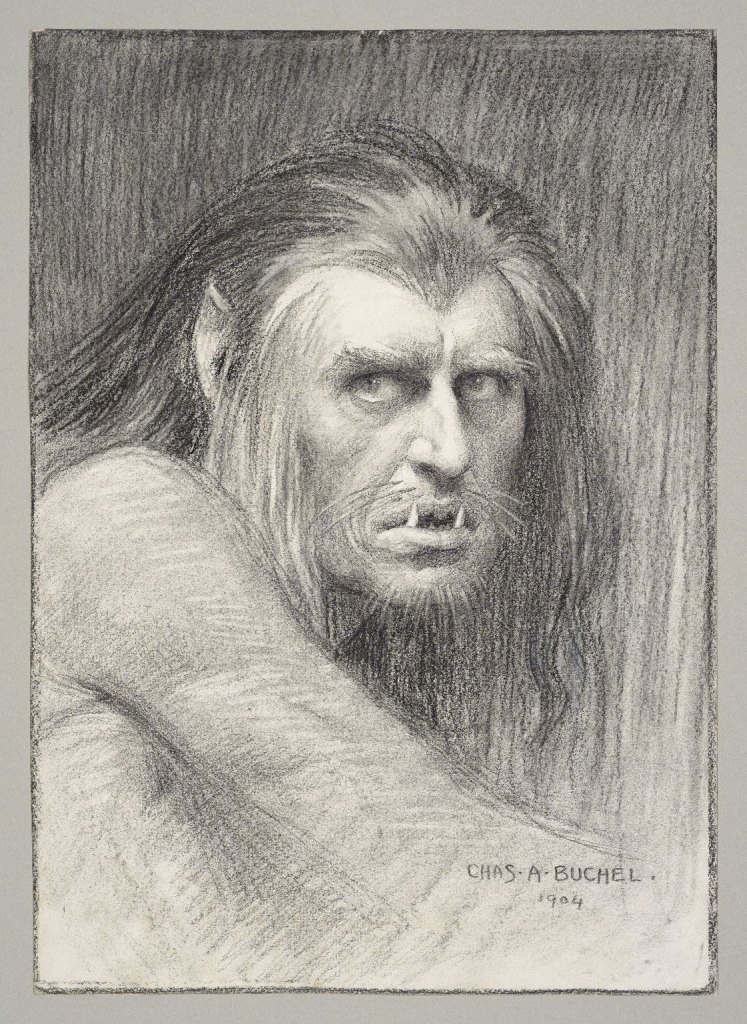

This blog performs an investigation of Caliban, a main character from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Caliban is a man of many contradictions. In Act 1 scene 2, he is introduced to as a “poisonous slave”, of a “vile race” and as “hagseed.” Other characters also remark on his appearance and demeanor, describing it as monstrous, yet the reader/audience is also briefly shown a different aspect of Caliban: one that is sensitive, articulate, intelligent. We see his poetry.

Perhaps one of the most famous, and beautiful, quotes by Caliban comes at a moment where he is lowering himself before Stephano and they both suddenly hear the invisible Ariel play music. Caliban asks if Stephano is afraid, and when Stephano denies that he is, Caliban says:

Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises,

Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep

Will make me sleep again; and then in dreaming

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that when I waked

I cried to dream again (III.ii.130–138)

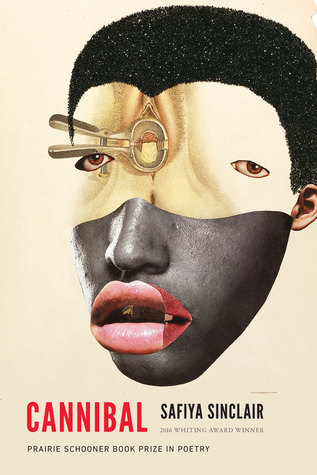

From a man-creature that seems to have debased himself completely comes a beautiful and articulate poem that is striking in its contrast. Caliban understands the island like few others do, in a way that no other character has described. His poem is so poignant because it reveals there is more to Caliban than meets the eye. And just as Caliban’s monstrous “otherness” is presented and juxtaposed alongside a rich and lovely eloquence, I have found other adaptations and interpretations of Caliban that manage to capture, examine, or challenge those two contrasting sides of monstrous and poetic. I respond to the various “poetry” (beauty, sensitivity, eloquence, humanity) of Caliban created by these artists, writers and actors, and attempt to understand how they interpret and connect to Caliban in The Tempest.

For your convenience, the adaptations have been archived into subheadings of word, image and performance. This is based on the way that Caliban is characterized and how his “poetry” is represented.